After the Second World War, several post-colonial governments seized foreign companies – Latin American oil fields, African ports, Middle Eastern refineries and more. They justified these moves as being in their national interest, seeking to regain control of sovereign assets from the erstwhile colonial owners.

Western commentators and media called it “expropriation” and a violation of the rule of law. It didn’t matter that, till then, they were exploiting these same colonies.

Yet, today, we see the Western democracies appropriating and freezing assets. And this too is being done in the “national interest”. Only this time it comes wrapped in nice legal language; sanctions, security reviews, or national emergency provisions.

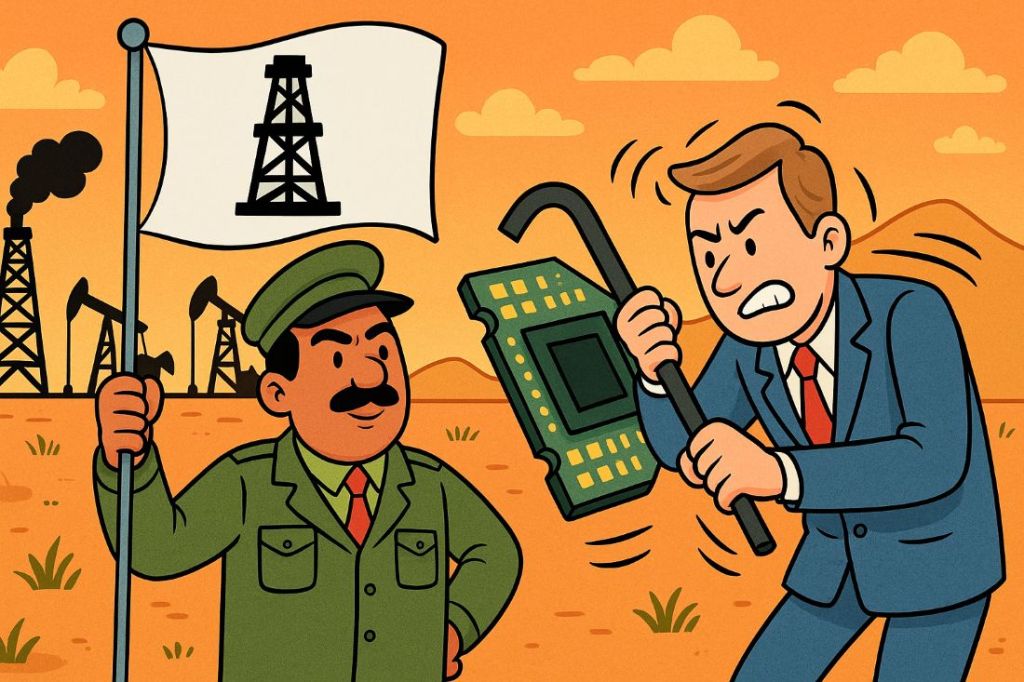

In September this year, the Dutch government forcibly acquired control of the Chinese-owned Nexperia facility in the Netherlands. Invoking the “Goods Availability Act,” it took over the plant without warning.

Nexperia manufactures chips used in automobiles, electronics, and other European industries. The company had broken no law; yet possible future supply constraints were cited as a “potential threat” to national security. This is like arresting someone in anticipation of a crime!

Resource nationalism was common in post-colonial states in the second half of the 20th century. In almost every continent, governments nationalised or “expropriated” assets. The most famous of these was in 1956, when Egypt nationalised the Suez Canal. Most oil-producing countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, Libya, and Iraq saw forced nationalisation of oil companies. Across the “developing” world, mineral assets and other kinds of businesses were nationalised.

These countries justified the moves as essential for security and independence from foreign domination. Even though many of these countries were run by unelected autocrats, their sovereignty concerns were often genuine.

Western commentators framed these as illegitimate, reckless, populist, anti-market, and a betrayal of investor confidence. Not only were they condemned, but there are instances of errant governments overthrown by Western-backed coups, notably Iran and Guatemala.

Fast-forward to the 2020s: The US and EU have frozen more than $300 b of Russian state assets. The UK forced the sale of a majority Chinese stake in British semiconductor company, FTDI. Canada, Germany, and Australia have blocked Chinese investment in several sectors. The US wants to forcibly acquire Tik Tok. And they sanction those who choose to do business with Venezuela, Iran or Russia.

Interestingly, the rhetoric is pretty much the same – sovereignty, national security, strategic autonomy.

The difference lies in form, not substance. Earlier expropriations were overt; today’s are institutionalised. Western democracies have legitimised such acts (in their own eyes) through carefully crafted laws and “due process.”

But is there really a difference?

Post-colonial regimes sought control over strategic resources; Western democracies seek control over strategic technologies. Then it was oil, copper, ports; now it’s chips, data, critical minerals, and algorithms.

In all cases, actions are taken in the “national interest.” Measures are justified as necessary and moral. And whether by dictator or elected ruler, compensation and legal recourse for the foreign owner are limited or symbolic.

I do not claim to know whether such actions are justified. National security can (and will), from time to time, override free markets. But the narrative is asymmetric. The difference between expropriation and “asset freeze,” between nationalisation and “divestment order,” is mainly semantic — and ideological.

Western economists created and promoted the concept of “sovereign risk” or “country risk” – and you can guess which countries are rated high and low. Maybe it’s time for a re-look.

If one were to create a sovereign risk indicator from a Chinese lens, it would look very different from the current Western-moderated indices. And those supposedly well-behaved adherents of law and order might well be the most risky.

Leave a comment